In January 2010, while they were inspecting the Iranian uranium enrichment reactor "Natanz" or "Natanz" as it is read, IAEA experts noticed abnormal activity in the rooms containing thousands of nuclear devices. Centrifuges that enrich uranium.

Normally, Iran replaced about 10% of its centrifuges annually, due to material defects or other technical problems. With about 8,700 centrifuges in the Natanz reactor at the time, it was only natural that about 800 centrifuges would be replaced over the course of the year.

But when the International Atomic Energy Agency reviewed the recordings of security cameras installed outside these rooms to monitor Iran's enrichment program, the experts were shocked when they counted the numbers. Engineers were replacing centrifuges at an incredible rate. By some estimates, nearly 2,000 centrifuges were replaced over the course of a few months.

The logical question that preoccupied the agency's experts at the time was: Why?

Iran was not required to disclose the reason for replacing the centrifuges, and at the same time the inspectors are not entitled to ask it officially, because their mission was limited to monitoring what happens to the nuclear materials in the reactor, and they have nothing to do with the equipment. But it was very clear that something was wrong with these devices.

What the inspectors and the Iranians didn't know was that the answer they were looking for was lurking somewhere within meters of them, buried within the "guts" of the reactor's computers.

The book Nobody's Army: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War, published in April of this year, is one of the most interesting books on military affairs that we can read. In addition to many stories about autonomous weapons, the writer tells us the story of what experts believe is the first cyber weapon in history.

The ghost

In June of 2010, it was fate that computer security professionals around the world discovered something unparalleled. This thing was a computer worm more advanced than anything the world had seen up to that time.

It is likely that it was the product of the work of a team of professional hackers, which may have taken months, if not years, to design it.

The worm dubbed "Stuxnet" is a form of malware that has long been anecdotes among cybersecurity professionals, but no one has seen it before. She was a ghost, but a ghost could do more than spy.

Stuxnet, which could steal and delete data, was also capable of destroying things, not only in cyberspace but in the physical world as well.

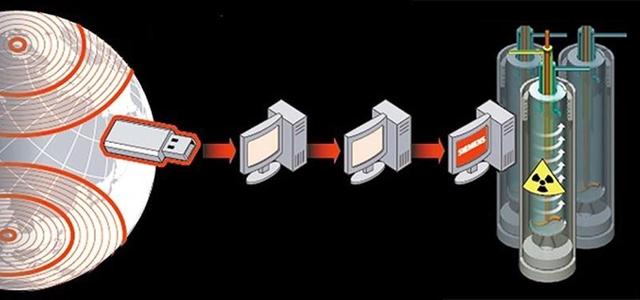

By spreading via USB flash drives, the first thing Stuxnet does when it infects the operating system is to give itself root access, which means unlimited access to the entire operating system. the system.

Stuxnet then hides inside the operating system using a real - not fake - security certificate from a reputable company, to hide itself from antivirus software. Hence, the Stuxnet mission begins.

Once it enters a single device, Stuxnet spreads to penetrate all devices connected to the same network, and then starts searching for a specific program, which is "Simatic Step 7" developed by the German company "Siemens", which manages programmable logic controllers (PLCs). PLC) used in the industrial automation process.

PLCs are used to control water valves, traffic lights, factories, pipelines, nuclear reactors and other automated tasks. Stuxnet has the ability to reprogram PLCs, and hide changes that have been implemented.

But Stuxnet was not looking for any PLC. Just like guided missiles, Stuxnet was looking for a very specific type of industrial control system, namely that of the frequency conversion drives used to control the speeds of centrifuges in nuclear reactors.

Homing!

If it does not find its target, the worm leaves the computer alone and self-destructs after two years. But if it finds the desired target, Suxnet activates itself and launches two encrypted "warheads", in the words of electronic security experts.

The first header, literally hijacking PLCs, taking control of them and changing their settings without anyone noticing. The other records regular industrial operations, before rebroadcasting them to the engineers of the target industrial facility sitting watching the integrity of the system, like a fake surveillance video during a bank robbery.

While Stuxnet secretly sabotages the industrial facility, the same worm is tinkering with the system to make it appear to anyone watching its safety that all is well.

Cybersecurity experts believe that Stuxnet was designed to hit a specific industrial target, which is Iran's Natanz uranium enrichment reactor. Of the approximately 100,000 computers worldwide infected by the worm, 60% of the infected devices are believed to be located in Iran and belong to facilities linked to Iran's nuclear enrichment programme.

Stuznet was able to destroy a large number of centrifuges in the Natanz reactor, causing a sharp decline in their numbers.

Cybersecurity experts suggest that the party that designed this worm is the United States or the Zionist entity, or both, but proving such speculation may be difficult in cyberspace, especially since everyone denies their relationship with this worm.

What's amazing about Stuxnet is that it has a huge amount of autonomy, because it was originally designed to work on air-gapped networks, which are networks that are not connected to the Internet for security reasons.

To access these fortified networks, Stuxnet needs to be inserted via USB or flash devices.

Once inside the device, the worm starts working on its own. It knows what it has to do, because it carries in its design all the tasks required to subvert the target system. Thus, Stuxnet works like a guided missile, just as the military chooses a target, and then Stuxnet attacks and engages.

Who is behind it?

In June 2013, retired General James Cartwright received a letter from the US Department of Justice informing him that he was under investigation, due to his possible role in leaking classified information about Stuxnet and very sensitive details about how he targeted Iranian nuclear facilities to the newspaper. The New York Times".

After hiding his identity, Cartwright, who is described as the mastermind of Stuxnet, revealed to a reporter for The New York Times that the computer worm that helped hinder Iran's development of nuclear weapons began to be developed during the administration of former President George W. Bush. Before being used to attack Iranian centrifuges immediately after Obama came to power.

At first, Cartwright denied being the source of the leak, but on October 17, 2016, he admitted that he lied to investigators and that he was the one who leaked information about the program that targeted Iranian infrastructure. On January 17, 2017, Obama issued a presidential pardon for Cartwright.

Regardless of this amnesty, (the bastard worm) remains a dazzling thing in an arms race that relies on technology, in which the powerful achieve huge victories in all parts of the earth with just the push of a button and sometimes without it, without leaving its place.