Giraffes need high blood pressure because of their height, but they avoid the huge health problems that people with high blood pressure suffer from, so how does that happen?

For most people, giraffes are just beautiful animals with long necks that attract the largest number of visitors to zoos or those who want to get pictures next to them during trips. But for specialists in cardiovascular science, it is much more than that, as it turns out that giraffes have succeeded in solving a problem that kills millions of people every year, which is high blood pressure.

Solutions to this problem, which scientists have only partially understood so far, include compressed organs, a change in heart rhythm, and blood storage.

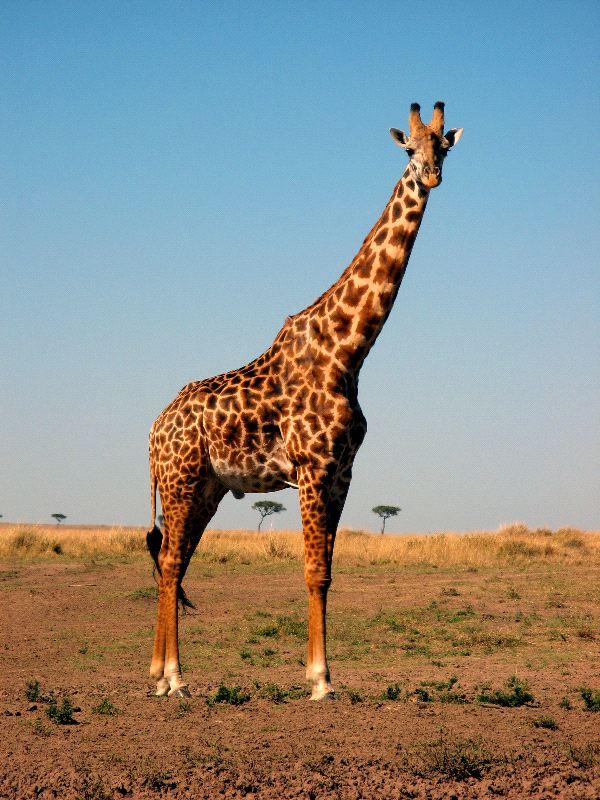

Giraffes suffer from a significant increase in blood pressure due to the high head height, which in adults rises about six meters (19 feet) above the ground, which is a very long distance for the heart to pump blood up against gravity.

In order to have a blood pressure of 110/70 in the brain - which is about normal for a large mammal - giraffes need a blood pressure in the heart of about 220/180.

Skip topics that may interest you and continue reading. Topics that may interest youtopics that may interest you. End

Although it doesn't bother giraffes, such pressure causes all sorts of problems for humans, from heart failure to kidney failure and swollen ankles and legs.

For people, chronic high blood pressure causes the heart muscles to thicken, and the left ventricle of the heart becomes stiffer and less able to fill again after each beat, which leads to a disease known as diastolic heart failure, which causes the person to become exhausted Shortness of breath and decreased ability to exercise.

Also, this type of heart failure is responsible for nearly half of the 6.2 million cases of heart failure in the United States today.

Skip the podcast and read onMorahakatyTeenage taboos, hosted by Karima Kawah and edited by Mais Baqi.

The episodes

The end of the podcast

When cardiologist and evolutionary biologist Barbara Natterson Horowitz of Harvard University and the University of California, Los Angeles, examined giraffe hearts, she found that the left ventricles had thickened, but without the sclerosis or fibrosis that occurs in humans.

The researchers also found that giraffes have mutations in five genes associated with fibrosis. Other researchers examining the giraffe genome in 2016 found several giraffe-specific genetic variants related to cardiovascular development and the maintenance of blood pressure and circulation.

In March 2021, another research group revealed the presence of giraffe-specific variants in genes responsible for fibrosis.

There is another trick that giraffes have to avoid heart failure, as the electrical rhythm of their hearts differs from that of other mammals.

Naterson Horowitz found that the ventricular filling phase of the heartbeat in giraffes extends for a longer time. This allows the heart to pump more blood with each beat, which allows the giraffe to run powerfully despite its thick heart muscle.

"All you have to do is look at a picture of a fleeing giraffe, and you will immediately realize that the giraffe has solved that problem," says Natterson Horowitz.

Naterson Horowitz is now turning her focus to another problem the giraffes seem to have resolved as well: high blood pressure during pregnancy, a condition known as pre-eclampsia.

In people, this can lead to serious complications including cirrhosis of the liver, kidney failure, and placental abruption. But giraffes have no problem with this, and Naterson Horowitz and her team hope to study the placenta of giraffes during pregnancy to see if they have unique adaptations that allow them to do so.

People with high blood pressure are also known to be prone to unpleasant swelling in the legs and ankles, because the high pressure forces water out of the blood vessels into the tissues. But you only have to look at the slender legs of the giraffe to know that they also solved this problem.

Why don't we see giraffes with swollen legs? And how are they protected from the enormous pressure? there?"

Giraffes reduce swelling with the same trick nurses use on patients by using 'support stockings'. With people, these stockings are tight, elastic pants that compress the leg tissue and prevent fluid buildup. Giraffes achieve the same thing through a tight roll of dense connective tissue.

Alker's research team tested this by injecting a small amount of saline solution under the fascia into the legs of four giraffes that had been anesthetized for other reasons. The team found that a successful injection required significantly more pressure in the lower leg than a similar injection in the neck, indicating that the fascia helped resist leakage.

Alkire et al. found that giraffes also have thick-walled arteries near their knees that may act as restrictions on blood flow. This can lower the blood pressure in the lower legs, just as a knot in a garden hose causes the water pressure to drop just past the knot. However, it remains unclear whether giraffes open and close arteries to regulate lower leg pressure as needed.

"It would be fun to imagine that when a giraffe stands there, it closes that sphincter muscle just below the knee, but we don't know," says Alkire.

Alker raises another question about these remarkable animals: When a giraffe raises its head after bending down to drink water, the blood pressure to the brain should drop rapidly - a state more severe than the dizziness that many people experience when they stand up suddenly, so why don't giraffes faint? ?

It seems that part of the answer to that question is that giraffes can prevent these sudden changes in blood pressure. In anesthetized giraffes whose heads can be raised and lowered with ropes and pulleys, Alkire found that blood pools in the large veins of the neck when the giraffes lower their heads.

This results in more than a liter (0.2 gallons) of blood being stored, which temporarily reduces the amount of blood that returns to the heart. With less blood available, the heart generates less pressure with each beat as the head descends. When the giraffe raises its head again, the stored blood suddenly rushes back into the heart, which responds with a powerful, high-pressure pulse that helps pump blood to the brain.

It is not yet clear whether this is what happens in awake, free-moving animals, although Alkire's research team has recently recorded blood pressure and flow from sensors implanted in free-moving giraffes and hopes to have an answer soon.

So, can we learn medical lessons from giraffes? None of these ideas has led to a definitive clinical treatment, but that doesn't mean it won't happen soon, says Natterson Horowitz.

Although some of the alterations may not be related to high blood pressure in humans, they may help biomedical scientists think about the problem in new ways and find new treatments for this very common disease.